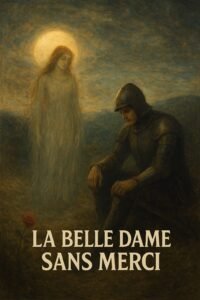

A Poem That Breathes Like a Dream

John Keats wrote La Belle Dame Sans Merci in 1819, but even now, the poem refuses to age. It lingers like a whisper caught between dream and nightmare. There’s something timeless in its brevity—just twelve stanzas, each a small sigh of beauty and despair.

The title translates to “The Beautiful Lady Without Mercy.”

Even before we meet her, we know she’s dangerous.

The poem opens with a question: “O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms?”—a stranger’s voice addressing a pale, lonely knight. He’s found wandering a desolate landscape where no birds sing, no grass grows. Something’s wrong. He’s alive, but barely.

Keats, that soft-voiced Romantic with eyes fixed on eternity, builds his tragedy with restraint. No loud grief, no moral sermon. Just a vision—a doomed knight and a mysterious woman whose beauty devours him.

The Knight and His Silence

Let’s start with the knight. He’s the human heart stripped bare—once strong, now wandering.

He has loved, and love has undone him.

The first few stanzas paint him as a ghost of himself: pale, haggard, alone among “the sedge… withered from the lake.” His armor is useless now. His story, as he tells it, sounds less like a confession and more like a trance.

He recalls meeting a woman “full beautiful—a faery’s child.”

That line alone shimmers with Keatsian tension: real or unreal, mortal or not, he doesn’t care. She sings to him, feeds him roots and honey, speaks a “language strange.” Love—or whatever shadow of it—overwhelms reason.

And here’s the thing: Keats doesn’t tell us whether the woman deceives him or whether he deceives himself. Reality and illusion are lovers in this poem, inseparable and cruel.

La Belle Dame — The Fatal Muse

She’s not a villain. Not exactly.

The “beautiful lady without mercy” is a mirror, reflecting desire itself.

Her gifts—roots, honey, and manna—sound like nourishment, but they’re really enchantments. She leads the knight to her “elfin grot,” a cave-like chamber that feels more like a tomb. There, she weeps and sighs, but for what? Pity? Passion? Manipulation? We’ll never know.

Keats’ genius is that she remains untouchable. A presence more than a person. Her power is her ambiguity. She embodies the eternal Romantic paradox: beauty that destroys, love that consumes, imagination that deceives.

When she whispers “I love thee true,” we believe her for a moment—then the dream breaks. The knight falls asleep and wakes to horror.

The Vision of the Pale Kings

The nightmare inside the dream: that’s the core of this poem.

While the knight sleeps, he sees “pale kings and princes too, pale warriors, death-pale were they all.” They warn him that he’s not the first victim. They, too, were seduced, abandoned, left hollow by the same merciless beauty.

It’s almost mythic—an ancient lineage of men undone by the same woman, or rather, the same desire. Keats paints it like a vision of universal heartbreak.

When the knight wakes, the world has died around him. The lush meadows are gone. The birds silent. Even time feels drained. The woman’s gone too, leaving him between life and death, still wandering, still haunted.

A Ballad of Emptiness

The structure of La Belle Dame Sans Merci is deceptively simple—each stanza a small, perfect box of melancholy. It follows the traditional ballad form, alternating between lines of iambic tetrameter and trimeter, with a steady ABAB rhyme.

But simplicity is Keats’ weapon. He strips away ornament until only rhythm and atmosphere remain. The repetition—“And no birds sing”—acts like a tolling bell. Each stanza folds back into the same desolate quiet.

This is poetry as haunting as it is melodic—music without mercy.

Keats’ Inner Landscape

Every poem Keats wrote in 1819 seems to face death with a strange tenderness—Ode to a Nightingale, Ode on a Grecian Urn, To Autumn. They all circle the same truth: beauty doesn’t last, but it’s all we have.

La Belle Dame Sans Merci carries that truth in miniature.

Keats was young, poor, and dying of tuberculosis when he wrote it. He had known love—especially with Fanny Brawne—but love for him was always shadowed by illness and fate. The beautiful lady, then, could be read as death itself—sweet, seductive, and without mercy.

The knight’s sleep resembles Keats’ longing for release. And when he wakes to emptiness, it’s almost prophetic. Keats would die two years later at twenty-five, his last words reportedly: “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.”

Symbolism and the Nature of Illusion

There’s no shortage of symbols here. The pale horse, the withered sedge, the “elfin grot”—all speak to decay and enchantment.

But look closer. The real symbol is the act of storytelling. The entire poem is a retelling: a stranger asks, the knight answers. And in that telling, his tragedy repeats itself. Like an echo, or a curse.

Keats seems to suggest that love stories—especially those of obsession—are doomed to replay forever. The telling is the haunting. Reality is that La Belle Dame Sans Merci isn’t just about a knight—it’s about the human appetite for beauty we can’t possess. Can you imagine that? Wanting something so perfect it unravels you?

That’s what Keats captures—not just romance, but the dangerous longing at its core.

Romanticism’s Dark Pulse

Keats was a Romantic poet, yes—but not the dreamy, rose-petal kind. His Romanticism had teeth. He saw beauty as both sacred and fatal. In La Belle Dame Sans Merci, the natural world mirrors the knight’s inner ruin. The withered lake, the barren hillside—all drained of life. The Romantic ideal of nature as healing is reversed here: nature suffers alongside him.

This inversion gives the poem its eerie power. It’s Romanticism on the edge of Gothic—a love song turning into a dirge.

The Beauty That Burns

The more one reads La Belle Dame Sans Merci, the less it feels like a poem about a woman and the more it feels like a warning about art itself. Beauty enchants. Beauty destroys. The poet, like the knight, serves something merciless.

Keats once wrote, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” But this poem quietly rebels against that idea. Here, beauty hides truth; it bewitches and betrays.

And yet… we keep reading. We can’t help ourselves. That’s the cruel magic of Keats—the ache feels exquisite.

Theme- The Stillness After the Song

When the final line falls—“And no birds sing”—it’s like the air itself stops. There’s no resolution, no awakening. The knight remains trapped in that liminal space between dream and death, just as we are after reading.

Keats offers no lesson, only atmosphere. But maybe that’s the point. Some poems aren’t meant to explain—they’re meant to haunt.

La Belle Dame Sans Merci is one of them. A perfect little ghost, humming endlessly in the ruins of our imagination.

And truly—what a way to be remembered.

FAQs About “La Belle Dame Sans Merci”

- What is the main theme of La Belle Dame Sans Merci?

It explores the fatal power of beauty, the fragility of love, and the tension between fantasy and reality. The poem is both a romance and a lament. - Who is the “Belle Dame”?

She’s a symbolic figure—sometimes read as a femme fatale, sometimes as death, sometimes as art itself. Her mystery is her meaning. - Why is the knight described as “alone and palely loitering”?

Because he’s trapped between life and dream, drained by his encounter. It’s a visual metaphor for emotional ruin. - Is the poem feminist or anti-feminist?

It’s neither. Keats isn’t condemning women; he’s portraying the consuming nature of desire. The “lady” is a metaphor, not a moral. - Why is this poem still relevant today?

Because we still chase illusions—of beauty, love, and perfection—knowing they might break us. Keats simply gave that truth a melody.